Reduction of Risk Potencial / 05

Make sure to:

- Describe the routes of transmission for nosocomial and healthcare-associated infections.

- Identify risks for nosocomial and healthcare-associated infections.

- Reinforce interventions to reduce risks for healthcare-associated infections.

Infection is the result from the entry and multiplication of a pathogenic microorganism in the tissues of a host, causing clinical signs and symptoms. When the infection is passed from one person to another, it is a communicable (also known as infectious or contagious) disease. Microorganisms residing on the skin are not usually pathogenic. However, they can cause serious infections when they penetrate deep tissues through surgery or invasive procedures, or when they are acquired by immunocompromised patients.

Infection is the result from the entry and multiplication of a pathogenic microorganism in the tissues of a host, causing clinical signs and symptoms. When the infection is passed from one person to another, it is a communicable (also known as infectious or contagious) disease. Microorganisms residing on the skin are not usually pathogenic. However, they can cause serious infections when they penetrate deep tissues through surgery or invasive procedures, or when they are acquired by immunocompromised patients.

Nosocomial infections originate in the hospital. Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) are those acquired in the process of receiving hospital care, which were not present or incubating at the time of admission. Healthcare personnel can transmit nosocomial microorganisms, but the infections they develop do not manifest until discharge (Berman et al., 2022). These can occur in hospitals, long-term care facilities, and outpatient clinics. HAIs also include occupational infections that can affect the staff (Sikora & Zahra, 2023).

The World Health Organization estimates that 7% of patients in high-income countries and 15% of patients in low- and middle-income countries who are admitted to the intensive care unit will acquire at least one HAI during their hospitalization (World Health Organization, 2022). Given the impact of these events, one of WHO's goals is that by 2030 all people accessing or providing healthcare will be safe from healthcare-associated infections. Therefore, it is developing the Global Strategy for Infection Prevention and Control (GSIPC) (World Health Organization, 2023). One component of the GSIPC is coordinating the various programs already in place for the prevention of HAIs.

3.1 Routes of Transmission

Diverse strategies have been implemented to eliminate healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), but none has been sufficient to eradicate them completely, as they continue to occur in both hospitalized patients and healthcare personnel. Nosocomial infections tend to occur within the first 48 to 72 hours after hospitalization or upon discharge. There are factors that favor their development such as immunocompromised patients, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, severe fungal and viral infections, invasive procedures, and failures in the application of universal precautions or in the prevention guidelines (Weintein, 2022). The microorganisms that cause nosocomial infections can come from endogenous sources (the clients themselves) or exogenous sources (the hospital environment and staff).

Diverse strategies have been implemented to eliminate healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), but none has been sufficient to eradicate them completely, as they continue to occur in both hospitalized patients and healthcare personnel. Nosocomial infections tend to occur within the first 48 to 72 hours after hospitalization or upon discharge. There are factors that favor their development such as immunocompromised patients, antibiotic-resistant bacteria, severe fungal and viral infections, invasive procedures, and failures in the application of universal precautions or in the prevention guidelines (Weintein, 2022). The microorganisms that cause nosocomial infections can come from endogenous sources (the clients themselves) or exogenous sources (the hospital environment and staff).

To persist and affect, pathogenic microorganisms require reservoirs in which to reside prior to infecting the host. The methods of transmission by contact are direct and indirect. Direct contact involves the direct passage from one patient to another. It generally occurs through skin-to-skin or mucosal contact, such as touching, kissing, or sexual intercourse. Droplet spread is also a form of direct transmission that occurs through droplets of more than 5-10 microns with a tendency to sediment rapidly. These are expelled by coughing, sneezing or talking. It requires a proximity to the source of less than one meter and the presence of oral and respiratory secretions containing pathogens (Berman et al., 2022). Examples include Diphtheria, Neisseria meningitidis, Pertussis, and Influenza viruses.

“Indirect transmission may be either vehicle-borne or vector-borne. A vehicle is any substance that serves as an intermediate means to transport and introduce an infectious agent into a susceptible host through a suitable portal of entry” (Berman et al., 2022). This occurs through contaminated surfaces (called fomites), such as handkerchiefs, toys, dirty clothes, cooking or eating utensils and surgical instruments.

The healthcare worker's hands can easily pick up microbes from a person, place, or thing and transmit them to other people, places, or things. Thus, almost any object in the healthcare environment (for example, a stethoscope or thermometer) can be a mode of indirect transmission of pathogens (Astle & Hobbs, 2019).

Examples of substances that act as vehicles include water, food (which can be contaminated by a food handler carrying hepatitis A virus), blood, serum, and blood products (Berman et al., 2022). In vector transmission, a vector (an animal or insect) serves as an intermediate means of transporting the infectious agent. In this type of transmission, infection occurs through the bite of, or contamination with the feces from, the animal or insect.

Airborne transmission occurs when very small particles (< 5 microns) are disseminated into the air, where they can remain for prolonged periods and be transported. Aerosol-generating medical procedures, such as intubation, bronchoscopy, aspiration, oropharyngeal sampling, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and autopsy, can contribute to airborne transmission. Examples: tuberculosis, measles, chicken pox, and the novel SARS-COV-2 virus which may be transmitted through the airborne route (Sikora & Zahra, 2023; Weintein, 2022).

Infections may also result from the administration of contaminated intravenous fluids. If the patient suffers from pathological processes, this might increase their susceptibility to acquiring an infection. Examples of these conditions include diabetes, renal insufficiency, extremes of life (childhood and late adulthood), surgical interventions, and immunocompromise (Weintein, 2022).

The immune responses of organisms are carried out by antibodies (immunoglobulins) and other defense cells. Antibody-mediated responses primarily defend against extracellular phases of bacterial and viral infections. The two main types of immunity are active and passive. In active immunity, the host produces antibodies in response to natural (from infectious microorganisms) or artificial (from vaccines) antigens. B cells become activated upon recognizing an antigen. A B cell can produce various antibody molecules, including IgM, IgG, IgA, IgD, and IgE. The presence of IgM in a laboratory test indicates a current infection. Before an antibody response becomes effective, phagocytic cells in the blood must bind to and ingest foreign substances. The rate of binding and phagocytosis increases in the presence of IgG antibodies, which indicate past infection and subsequent immunity.

Cell-mediated defenses, also known as cell-mediated immunity, are produced through the T-cell system.

Following exposure to an antigen, lymphoid tissues release numerous activated T cells into the lymphatic system. These T cells then enter the general circulation. There are three main groups of T cells: 1) Helper T cells, which assist in immune system functions; 2) Cytotoxic T cells, which attack and kill microorganisms and sometimes the body's own cells; and 3) T cells that can suppress the functions of both helper and cytotoxic T cells. When cell-mediated immunity is lost, as in the case of HIV infection, an individual becomes defenseless against most viral, bacterial, and fungal infections (Berman et al., 2022).

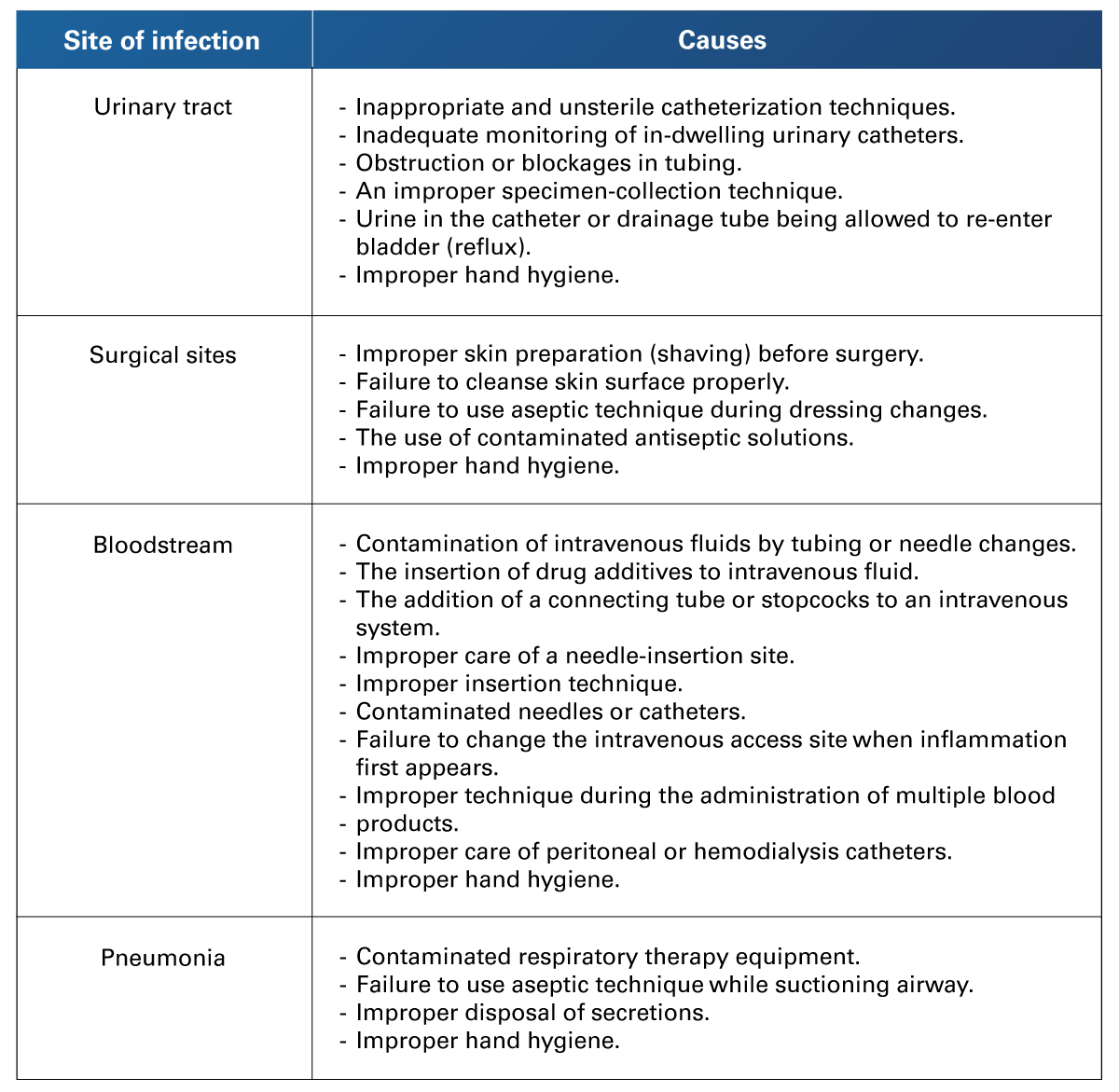

A host may acquire an infection due to susceptibility determined by age, heredity, predisposition, high-stress levels, poor nutritional status, current medical treatment, and pre-existing diseases. Regarding procedures performed on patients, infections are primarily caused by the breakdown of the body's natural defense barriers. The most common healthcare-associated infections are urinary tract infections (associated with the use of catheters or probes), vascular access infections, surgical site infections, bacteremia, and pneumonia, often associated with the presence of an endotracheal tube and mechanical ventilation. Health institutions must establish and implement specific and direct strategies to prevent, detect, track, and control these infections. All staff (including nurses) must know and follow them.

3.2 Complications

According to Weintein (2022), the main nosocomial infections are urinary tract infections, vascular access infections, surgical site infections, bacteremia and pneumonia associated with endotracheal tubes and mechanical ventilation. Urinary tract infections represent 10% of total HAIs, and among these, 3% of patients develop bacteremia. These infections are related to the handling of installed catheters or to unattended precautions prior to installation. Each day of catheter permanence generates a 3-7% risk of infection. Pathogenic microorganisms can travel from the perineum and digestive tract to the periurethral space. Intraluminal contamination can also result from cross-infection due to irrigation or improper handling of the drainage bag. The most frequently reported pathogens in urinary tract infections are Escherichia coli, gram-negative bacilli found in hospitals, Enterococci, and Candida.

According to Weintein (2022), the main nosocomial infections are urinary tract infections, vascular access infections, surgical site infections, bacteremia and pneumonia associated with endotracheal tubes and mechanical ventilation. Urinary tract infections represent 10% of total HAIs, and among these, 3% of patients develop bacteremia. These infections are related to the handling of installed catheters or to unattended precautions prior to installation. Each day of catheter permanence generates a 3-7% risk of infection. Pathogenic microorganisms can travel from the perineum and digestive tract to the periurethral space. Intraluminal contamination can also result from cross-infection due to irrigation or improper handling of the drainage bag. The most frequently reported pathogens in urinary tract infections are Escherichia coli, gram-negative bacilli found in hospitals, Enterococci, and Candida.

Regarding vascular access-related infections, 10 to 15% of nosocomial infections occur with central venous catheters being the most frequent, with a mortality rate of 12 to 25%. The infection originates when pathogens migrate from the insertion point outside the lumen to the catheter tip, typically within a week of insertion. Intraluminal infection can also occur due to contamination of the catheter ports. The most common pathogens for this route are coagulase-positive staphylococci, S. aureus, Enterococci, gram-negative bacilli and Candida.

Ventilator-associated pneumonias (VAP) account for 25-35% of all nosocomial lower respiratory tract infections. Most cases are due to aspiration of endogenous or hospital-acquired oropharyngeal organisms or gastric flora. The attributable mortality rates suggest that the risk of dying from nosocomial pneumonia is related to comorbidities, antibiotic comorbidities, inadequate antibiotic treatment, and the involvement of specific pathogens (in particular: Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Acinetobacter).

The risk factors for nosocomial pneumonia include those conditions that aid to increase the colonization by potential pathogens. These include prior antimicrobial therapy, contaminated ventilation equipment, and decreased gastric acidity. Also included are the conditions that facilitate aspiration of oropharyngeal contents into the lower respiratory tract, as happens with intubation. Finally considered are also the conditions that reduce pulmonary defense mechanisms and allow the aspiration of pathogens. For example, patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or upper abdominal surgery (Weintein, 2022).

Wound infections constitute 17% of nosocomial infections. On average, wound infection has an incubation period of 5-7 days longer than many postoperative stays. Today, many operations are performed on an outpatient basis, so their incidence is difficult to assess. These infections are usually caused by endogenous-acquired flora or hospital-acquired and are sometimes due to the airborne spread of skin flakes, from surgical equipment that may reach the wound or environmental sources. In general, the usual risks of postoperative wound infection are related to the surgeon's technical skill, underlying diseases (like diabetes mellitus or obesity), advanced age, inappropriate timing, the presence of drains, prolonged preoperative hospital stays, shaving of operative sites with a razor the day before surgery, and prolonged surgical time.

The most frequent pathogens in postoperative wound infections are S. aureus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, enteric and anaerobic bacteria. In rapidly progressive postoperative infections, which manifest within 24-48 hours after surgery, the level of suspicion for group A streptococcal or clostridial infection is high. The diagnosis of infections in prostheses, such as orthopedic implants, can be complicated when the pathogens are encapsulated in biofilms attached to the prostheses. Treatment of postoperative wound infections requires adequate source control, like drainage or surgical removal of infected or necrotic material, and antibiotic therapy directed at the most likely or laboratory-confirmed foci of infection.

3.3 Prevention

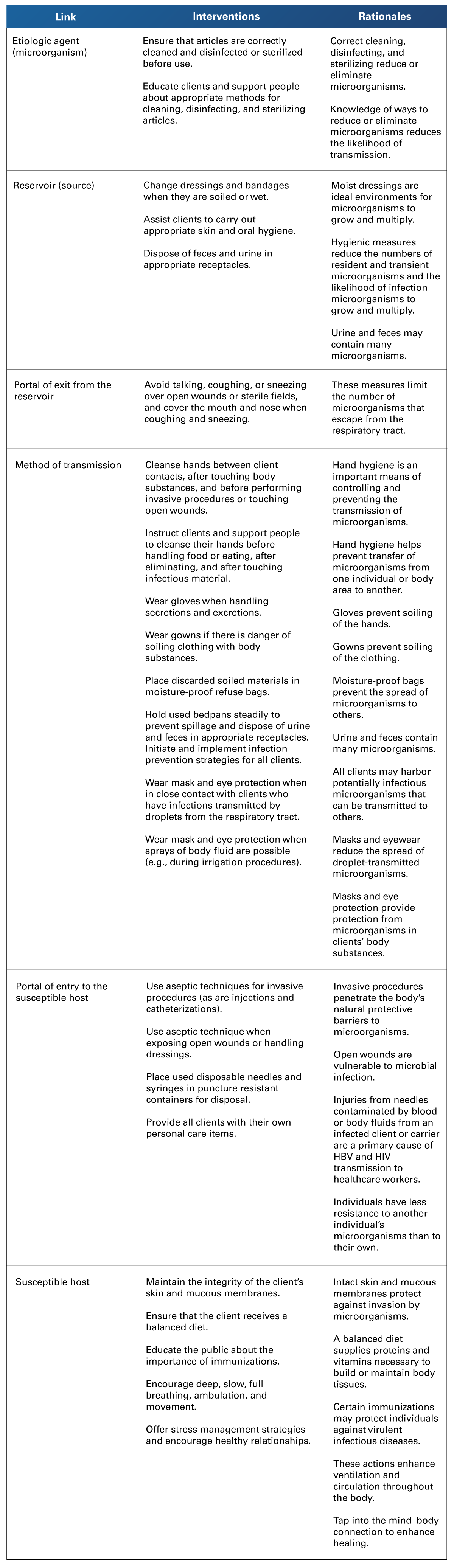

Since nosocomial infections follow basic epidemiological patterns, prevention and control measures can be implemented. As described in the previous section, nosocomial pathogens have reservoirs, are transmitted by different routes, and require susceptible hosts. They may be present on inanimate surfaces and in living beings. Cross-infection is the most common mode of transmission that involves contact between a susceptible host and usually a contaminated inanimate object, such as equipment, instruments, and environmental surfaces. This is often the result of contaminated hands that are not washed, which contaminates the object or environment (Weintein, 2022). In this regard, hand washing by healthcare personnel plays a very important role in preventing cross-infection. However, there is still resistance to this practice due to factors such as skin irritation caused by frequent washing, as well as lack of time or adequate infrastructure.

Since nosocomial infections follow basic epidemiological patterns, prevention and control measures can be implemented. As described in the previous section, nosocomial pathogens have reservoirs, are transmitted by different routes, and require susceptible hosts. They may be present on inanimate surfaces and in living beings. Cross-infection is the most common mode of transmission that involves contact between a susceptible host and usually a contaminated inanimate object, such as equipment, instruments, and environmental surfaces. This is often the result of contaminated hands that are not washed, which contaminates the object or environment (Weintein, 2022). In this regard, hand washing by healthcare personnel plays a very important role in preventing cross-infection. However, there is still resistance to this practice due to factors such as skin irritation caused by frequent washing, as well as lack of time or adequate infrastructure.

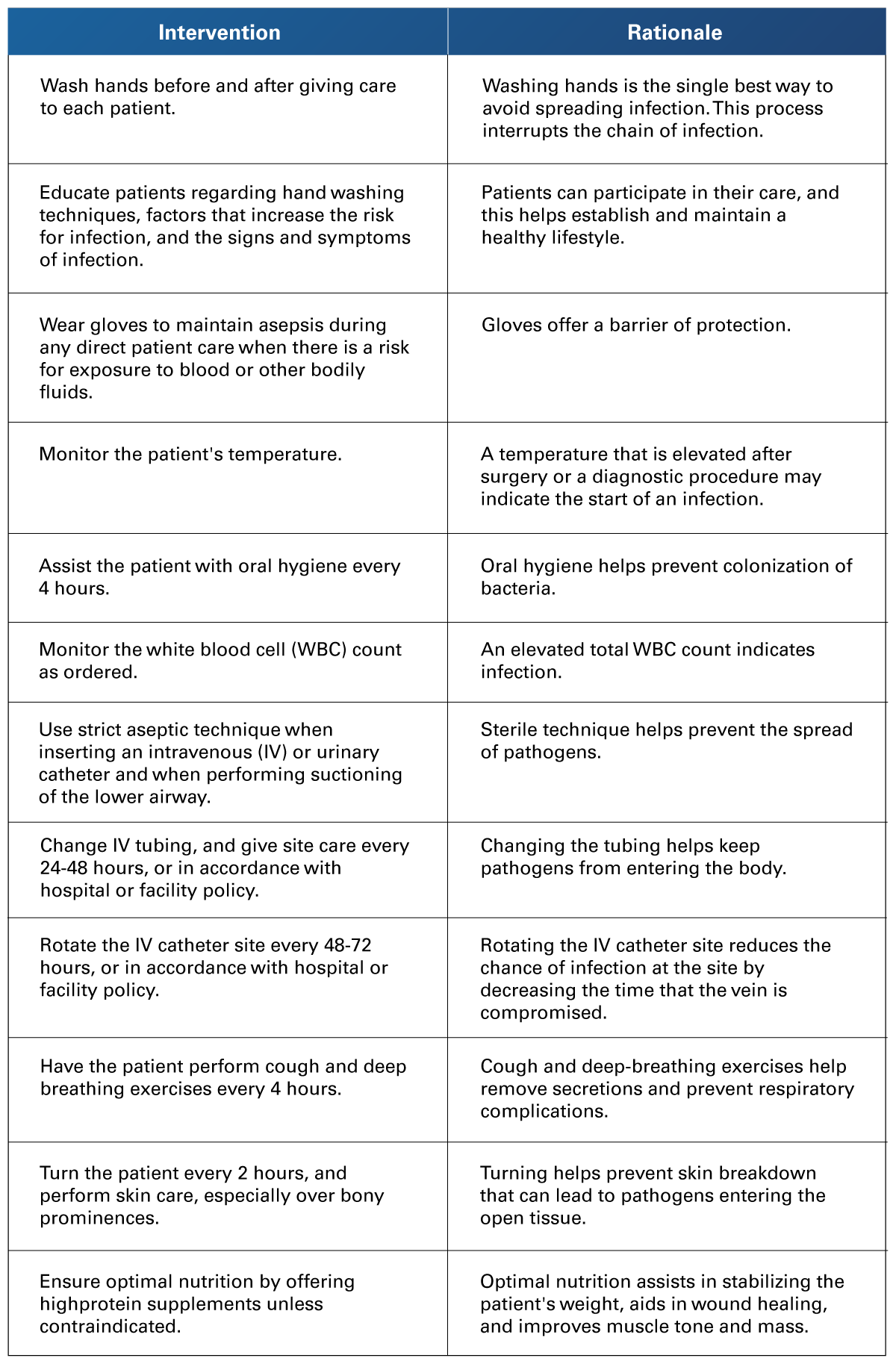

Proper hand hygiene is a crucial element for any effort towards infection prevention. The Standard Precautions (SP) should be followed during key moments to procure lower incidence numbers for HAIs. Standard Precautions are used in any situations involving blood, body fluids, excretions, and secretions (except sweat), non-intact skin, and mucous membranes. SP include (a) hand hygiene; (b) use of personal protective equipment (PPE), which includes gloves, gowns, eyewear, and masks; (c) safe injection practices; (d) safe handling of potentially contaminated equipment or surfaces in the client environment; and (e) respiratory hygiene or cough etiquette that calls for covering the mouth and nose when sneezing or coughing, proper disposal of tissues, and separating potentially infected individuals from others by at least 1 m (3 ft) or having them wear a surgical mask. Thus, attention should be given to risk assessment related to client symptoms, care, and service delivery, including screening for infectious diseases, fever, respiratory symptoms, rash, diarrhea, excretions, and secretions (Berman et al., 2022).

Consider risk reduction strategies using personal protective equipment (PPE), environmental cleaning, washing, disinfection, sanitization, and sterilization of single-use equipment or materials, waste management, safe sharps handling, client positioning, and healthy workplace practices. Healthcare organizations should also consider the education of healthcare professionals, clients, families and visitors regarding basic infection reduction measures. These practices reduce the risk of acquiring an infection from exposure during care to fluids, blood and material resulting from the same care.

Isolation precautions are designed to contain pathogens in one area, usually the patient's room. Only patients infected or colonized with certain highly transmissible or epidemiologically significant pathogens are placed under isolation precautions. These precautions are followed in addition to routine practices. Isolation precautions are categorized in three categories: airborne, droplet, and contact precautions (Astle & Hobbs, 2019).

In relation to the prevention of the main nosocomial infections that occur, the specific actions that can help prevent them are the following. To reduce the incidence of urinary tract infections, care should be taken in the handling of the urethral catheters from the time they are installed to avoid contaminating them. Also, fixing them according to the sex of the patient has been noted to decrease infection rates. In men, they should be fixed on the anterior aspect of the thigh. In women, they should be fixed on the internal aspect of the thigh. To avoid reflux of urine into the bladder, when it is required to mobilize the patient, the catheter should be clamped, and the bag should be placed at a lower height than the bladder (but never on the floor). The collection bag should never be more than 80% full. Assessment of the need to keep the catheter in place should be frequent and it should be removed as soon as possible.

Also, to prevent pneumonia due to aspiration of oropharyngeal flora into the lungs, mouth washings should be performed, and oropharyngeal secretions should be suctioned regularly so that they do not fall by gravity into the trachea and reach the lungs. Also, constant drainage of the ventilator hoses should be practiced, so that condensation water does not flow into the endotracheal tube, especially when moving the patient.

Regarding the prevention of surgical site infections in the preoperative care, it should be corroborated that the patient's blood glucose levels are below 200mg/dl. Likewise, it should be avoided to shave the surgical area with a razor. It is a mandatory safety practice to verify the sterility of the instruments and avoid situations that prolong the surgical time. In the postoperative period, unnecessary efforts should be avoided, and the patient and their relatives should be educated about wound care.

Regarding infections related to vascular access and monitoring, the catheter and infusion equipment must not be contaminated from the time of installation until the catheter remains in place for several days. The time of permanence of short peripheral catheters is according to current regulations generally no longer than 72 hours. In peripheral and central catheters, cures should be performed according to regulations, with antiseptics, keeping them fixed with transparent dressings. Watching out for signs of infection is important. These could be flushing, heat, swelling and presence of secretion. If any of them appear, the catheter should be removed.

Table 1

Sites of infection and Causes of Health Care–Associated Infections

Retrieved from Astle, C. M., & Hobbs, D. (2019). Canadian Fundamentals of Nursing. Elsevier.

Retrieved from Astle, C. M., & Hobbs, D. (2019). Canadian Fundamentals of Nursing. Elsevier.

Table 2

Nursing Interventions That Break the Chain of Infection

Retrieved from Berman et al. (2022). Kozie & Erb´s Fundamentals of Nursing: Concepts, Process and Practice. Pearson Education Limited.

Retrieved from Berman et al. (2022). Kozie & Erb´s Fundamentals of Nursing: Concepts, Process and Practice. Pearson Education Limited.

Table 3

Prevention of Infection

Retrieved from Yoost, B. L., & Lynne, C. (2021). Fundamentals of Nursing E-book: Active Learning For Collaborative Practice. Elsevier.

Retrieved from Yoost, B. L., & Lynne, C. (2021). Fundamentals of Nursing E-book: Active Learning For Collaborative Practice. Elsevier.

The concepts described in this section broadened the knowledge of the chain of transmission of infections. The main affectations that correspond to infections related to health care and the interventions that help to prevent or avoid them were also analyzed. Also, the importance of the application of Standard Precautions to reduce the risk that the nurse has when taking care of patients, which could represent a risk of contagion for a disease. All of these are very important to obtain the Certification of the NCLEX Examination.

The concepts described in this section broadened the knowledge of the chain of transmission of infections. The main affectations that correspond to infections related to health care and the interventions that help to prevent or avoid them were also analyzed. Also, the importance of the application of Standard Precautions to reduce the risk that the nurse has when taking care of patients, which could represent a risk of contagion for a disease. All of these are very important to obtain the Certification of the NCLEX Examination.

- Astle, C. M., & Hobbs, D. (2019). Canadian Fundamentals of Nursing, 2395-2492. Elsevier.

- Berman, A., Snyder, S. J., & Frandsen, G. (2022). Kozie & Erb’s Fundamentals of Nursing: Concepts, Process and Practice, 693-726. Pearson Education Limited.

- Sikora, A., & Zahra, F. (2023). Nosocomial Infections. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32644738/

- Weintein, R. A. (2022). Clinical Syndromes: Healthcare-associated Infections. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine (20th ed.). 1020-1029. McGraw Hill Education.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Global Report on Infection Prevention and Control. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/354489/9789240051164-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- World Health Organization. (2023). Global Strategy on Infection Prevention and Control. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/gsipc/who_ipc_global-strategy-for-ipc.pdf?sfvrsn=ebdd8376_4

- Yoost, B. L., & Crawford, L. R.(2021). Fundamentals of nursing E-book: Active learning for collaborative practice. Elsevier Health Sciences.

The following links do not belong to Tecmilenio University, when accessing to them, you must accept their terms and conditions.

Readings

- Government of the Republic of Trinidad & Tobago through the Ministry of Health. (2020, June). Infection Prevention and Control Guide to Best Practices: Environmental Cleaning Prevention of Infections in All Health Care Facilities. https://health.gov.tt/sites/default/files/2022-03/PAHO%20MoH%20Manual_Environmental%20Cleaning.pdfCengage

Videos

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Hand Hygiene Saves Lives [Video]. CDCP. https://www2c.cdc.gov/podcasts/media/mp4/HandwashingVideo-Engl_OC.mp4

La obra presentada es propiedad de ENSEÑANZA E INVESTIGACIÓN SUPERIOR A.C. (UNIVERSIDAD TECMILENIO), protegida por la Ley Federal de Derecho de Autor; la alteración o deformación de una obra, así como su reproducción, exhibición o ejecución pública sin el consentimiento de su autor y titular de los derechos correspondientes es constitutivo de un delito tipificado en la Ley Federal de Derechos de Autor, así como en las Leyes Internacionales de Derecho de Autor.

El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, fragmentos de eventos culturales, programas y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, es exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos, y cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por UNIVERSIDAD TECMILENIO.

Queda prohibido copiar, reproducir, distribuir, publicar, transmitir, difundir, o en cualquier modo explotar cualquier parte de esta obra sin la autorización previa por escrito de UNIVERSIDAD TECMILENIO. Sin embargo, usted podrá bajar material a su computadora personal para uso exclusivamente personal o educacional y no comercial limitado a una copia por página. No se podrá remover o alterar de la copia ninguna leyenda de Derechos de Autor o la que manifieste la autoría del material.